How to Overcome Price Anchoring

Part 1: Diagnosis

Many investors struggle to add to a position that has run up (or sell a position that’s in the red). Rather than focusing on the future prospects of the investment, they focus on their current cost basis. This phenomenon is known as price anchoring, and even otherwise very rational people can struggle with this bias causing them to miss out on great buying opportunities. That’s no good if you’re investing for financial gain.

If you’ve struggled with price anchoring yourself, I hope you’ll find this “How to Overcome Price Anchoring” series helpful.

Diagnosing the Problem

In my view, price anchoring is a symptom of an inconsistent approach to evaluating the attractiveness of an stock at different price points.

Let’s go back to the basics for a second. What makes an investment attractive?

Its future returns.

If you know the future returns at a given point in time, it is easy to recognize that price anchoring purchases at a higher price can yield not only acceptable annualized returns, but higher annualized returns than an investment at a lower price over a given time period.

Now, usually I advocate for a longer and more fundamental view of a stock, but suppose for a moment that for a particular stock you know exactly what the price will be in three years for a stock. I know, I know. That’s impossible. But hear me out.

If you know the future returns at a given point in time, it is easy to recognize that price anchoring purchases at a higher price can yield not only acceptable annualized returns, but higher annualized returns than an investment at a lower price over a given time period.

Price anchoring disappears.

An Example

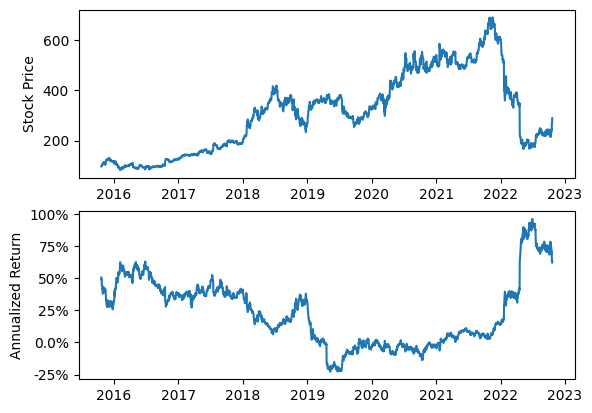

Let me illustrate using Netflix, ticker NFLX, as an example. Below is a plot of the NLX stock price and its annualized future returns over the next three years.

Despite paying three times the price of the first investment, the second investment was better.

If you bought NFLX at the start of the charted period (in late 2016) at a price of 97.32 USD, you would have had an annualized return of about 51% over the following three years.

However, if you bought at the end of the charted period (in late 2022) at a price of 289.57 USD, you would have had an annualized return of 62% over the following three years.

Despite paying three times the price of the first investment, the second investment was better over a three year period.

Problem Solved, Right?

If only. In practice, no one knows the future return of a stock, but I hope I’ve been successful in illustrating that the source of the problem is the lack of a framework for evaluating the attractiveness of a stock at different price points.

The source of the problem is the lack of a framework for evaluating the attractiveness of a stock at different price points.

While we cannot know the future returns of a stock, we can make an effort to estimate it. In the next post, I’ll introduce three methods for estimating future returns:

Two commonly used methods in finance.

A method suggested by Warren Buffett that I use myself.